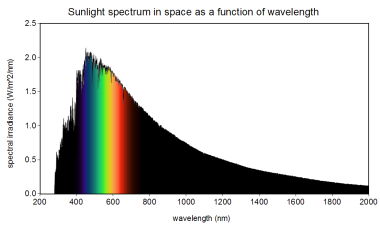

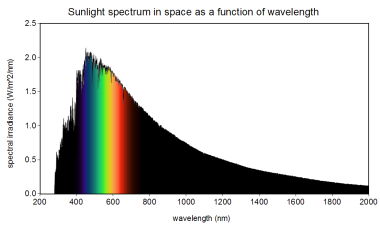

Why are the graphs for the distribution of light from the Sun as a function of (a) frequency and (b) wavelength not exactly reversed? ( www.wtamu.edu )

You are only browsing one thread in the discussion! All comments are available on the post page.